Aerobatics notation

Good example of evolution from iconic to abstract and from verbose to succinct

Aerobatics is the art of making an aeroplane dance: “loops, rolls, and other feats of spectacular flying performed in one or more aircraft to entertain an audience on the ground”, says the online dictionary. We were momentarily surprised to discover that there was a formalised notation; didn’t the pilot just throw the plane around for a bit? But of course there is. Just like other similar sports, especially competitive ones – acrobatics, gymnastics, high-level dancing, and so on – a turn is built from components, and the components have names.

But first the components have to be identified.The development of the notation used today seems to be a prime example of the conjectured lifecycle that we describe in Chapter XXX (7?). Stage 1:

When aerobatics first came into being in the 1920s, there was no good method for pilots to explain to others what they were going to fly. Some used their own method of shorthand notations, others would describe the manoeuvre with various words and phrases. (From http://www.iacchapter26.org/aresti.html on the website of Chapter 26 of the International Aerobatics Club; as are the next few extracts.)

At that point in time, we’re looking at the start of the notational lifecycle, simple description. Sloppy rather than pedantic; incomplete vocabulary, covering onlythe immediate tasks in hand; probably high viscosity, since no specialised editors would be available; good visibility.

But as the sport of aerobatics began to mature and spread into international competition, the need for a standardised method to describe aerobatic flight manoeuvres grew due to language differences. (Ibid)

This takes us to Stage 2, which we have called the ‘first flowering’, when an individual notation becomes widely adopted; and that in turn leads to stage 3, when the notation becomes rigidified and formalised:

In 1961, the Spanish pilot José Luis de Aresti published an aerocryptographic system to describe aerobatic manoeuvres that broke down individual pieces into lines, curves and rotational elements. This Sistema Aresti, or Aresti System, was adopted by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (WorldAir Sports Federation or FAI) as the official method of aerobatic sequence description at the World Aerobatic Championships inBilboa, Spain in 1964. Today, the Aresti System – called Arestifor short – is in use worldwide. (Ibid.)

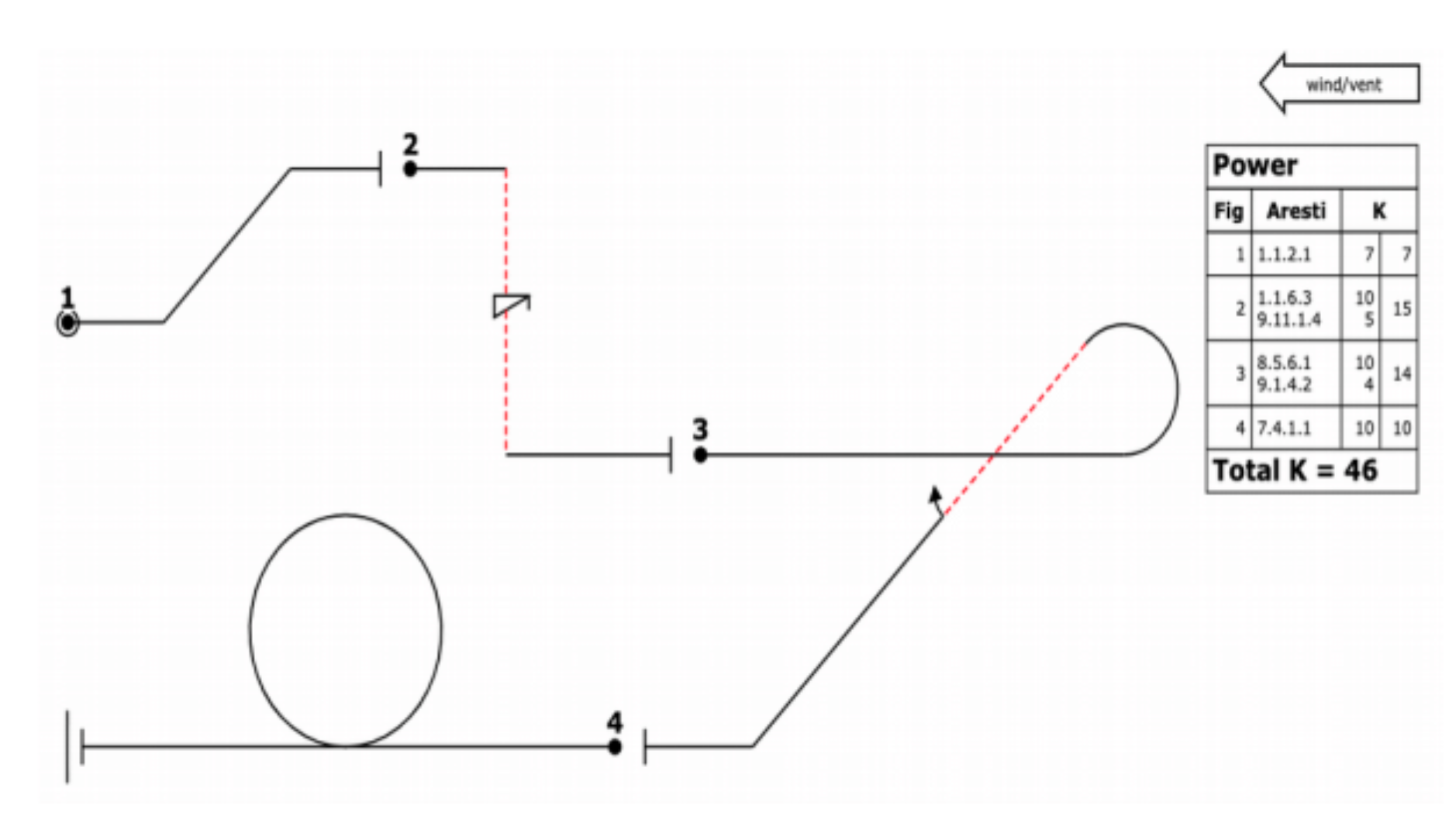

At this point we need to see an example. Figure 1. shows a short sequence of very simple manoeuvres. (In competitions, the sequences are likely to be twice as long and the manoeuvres much more complex and more skilful – but we only need to illustrate how the notation works and how it developed.)

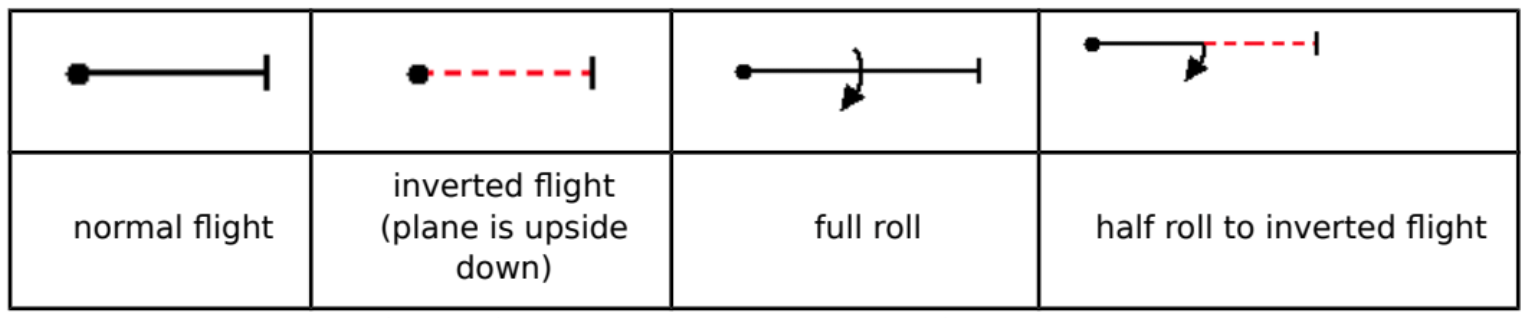

Aresti’s notation breaks down aerobatic figures into lines, curves, rolls, and similar basic elements, which are grouped into ‘families’ and assigned index numbers. First we need to know some basic elements; they are presented as stylised, quasi-pictorial diagrams, with very good closeness of mapping (see Figure 1.) although the closeness of mapping is decreased by the convention that inverted flight is shown as a dotted red line. Still, that is highly discriminable and is easy to learn.

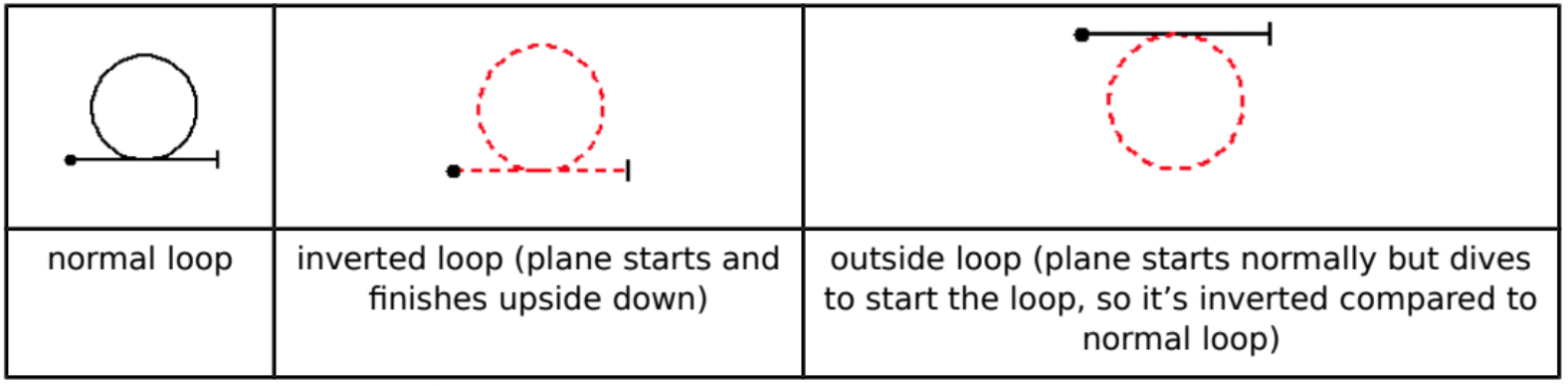

Loops also have good closeness of mapping:

The discriminability breaks down somewhat for turns (Figure 3.) but it is claimed that “Turns and rolling circles can be distinguished from loops by their ovoid shape” (https://www.slopeaerobatics.com/articles/an-introduction-to-slope-aerobatics/aresti-notation-tutorial/).

The pictorial diagrams are not, however, the complete Aresti notation. They areillustrations of it. The notation proper is an index, arrived at by dividing the list ofpossible components into nine families (one of which is now disused) and thenlisting possible variations of each component within each family. The entire list ispublished at intervals as the ‘Aresti catalogue’, and a particular figure is locatedin this lengthy list as follows:

All the basic figures in Families 1 to 8 are defined inaccordance with a 3-number system [family 9 is a 4-numbersystem]. The first number indicates the Family to which thefigure belongs. The second figure shows the row, and the thirdthe column, in which the figure is placed. The numbers areseparated by dots.FAI Aresti Catalog version 2003-1 p. 10

So the loops ofFigure 2.are catalogued as: normal loop,7.5.1; inverted loop,7.5.2; and outside loop as7.5.3. (We have not described the difficulty score, or ‘K factor’, associated with each figure, as not being germane to our discussion here.) The successive components of the sequence shown inFigure 1.are catalogued as: component 1,1.1.2.1; component 2,1.1.6.3, 9.11.1.4; and so on.

Very clearly we are now at Stage 3, the rigidifying stage. As a reminder, here isour characterisation of Stage 3:

In an attempt to improve consistency, rules are made explicit. The vocabulary is defined, the syntax is defined, the possible relationships between entities are defined, all in an effort to reduce slop and improve error-checking. The notation gets more pedantic and harder to use, although it’s more likely that a syntactically correct document means what its creator intended. If computer-based editing environments are developed, there will be even greater pressure towards rigidity. A sloppy notation is hard to deal with by program. (See chapter ?7)

Unfortunately, although the Aresti catalogue numbers succeed in their aim of supplying a well-defined vocabulary, they do so at a cost. The strings of digits are long-winded –verbose, in CDs terms – and hard to distinguish: they are not easily discriminable. There is no provision for abstraction, so there is no way to reduce the verbosity. Far from having a high closeness of mapping, there is no apparent relationship at all between the catalogue number for a figure, and the actual figure; and as there is no secondary notation of any sort, there is no possibility of helping the reader. In these conditions, we would expect that specifying a sequence by means solely of the catalogue numbers, without accompanying diagrams, would be unacceptably error-prone; and as the notation contains no self-description of any kind (such as the check-digit systems described in the essay on Codings Etc) errors will not automatically be detected. We would anticipate errors such as typing 1.2.1.1 for 1.1.2.1. Errors can be found by using each string of digits to locate a figure in the catalogue by its family, row, and column, and comparing that figure to an accompanying sketch of the intended meaning, but that will be a slow and tedious job.

There is a more insidious type of error that could easily occur. The Aresti notation is a history-sensitive notation. To remind the reader (actually, to tell the reader – we haven’t yet defined history sensitivity),in a history-sensitive notation, an item may be syntactically well-formed but it may be semantically unacceptable, because of what has gone before. Chess is a history-sensitive notation, because the instruction to castle, O-O, is always syntactically well-formed but is only semantically acceptable if neither king nor rook has yet made a move. Adding notes in common practice staff notation of music is not history-sensitive because any note may be added at any time, regardless of what notes have been written before. (It might not be humanly playable, but that’s not the issue – and anyway, computerised digital pianos have no restrictions of finger length!) The figures of flying have sequence constraints limiting what can be achieved. For example, a normal loop (Figure 2.) can only be entered from normal flight, with the aircraft the right way up, and likewise an inverted loop can only be entered if the aircraft is in inverted flight. Writing7.5.2(an inverted loop) will be an error if the notation up to that point has left the aircraft in normal flight. There is no way to detect such an error merely by syntactic inspection.

Finally, the figures present issues for computerised versions of the notation. It must be remembered that in 1920 there was, of course, no such thing as a computer, so no provision was made for possible transcription difficulties; nevertheless, in a computerised age, this lack will increase the pressure for notational evolution.

What happens next? We argue that in Stage 4 “The stresses of using a rigid notation cause ‘decoupling’, in which a complementary notation is introduced asa sketching tool, before transcribing the sketch into the target notation”. In the present case, that complementary sketching notation was introduced contemporaneously with the catalogue, as the quasi-pictorial illustration, so no need for a further development. But also, we say, “If the notation is computer-based, a patchwork of improved helper tools appears, which reduce local viscosity; history mechanisms appear to help back-track when needed. Syntax-colouring or other forms of supplementary recoding might be introduced if we’re on to the later cycles,” and that indeed has been the story. The helper tool in this case is an online editor, OpenAero (https://openaero.net/), which makes it surprisingly easy to edit the sequence diagrams and to insert or to remove components or change the individual figures.

The new notation was originally called OLAN (One Letter Aerobatic Notation), released in 2011 but eventually superseded by the OpenAero version, whichextended the notation and provided a good editor. The primary view is the diagram, as shown above, but the Aresti catalogue index numbers are automatically generated as well.

We will illustrate the OpenAero notation with the sequence of Figure 1., which is written:

d iv.s c oOpenAero notation for the sequence of Figure 1. Each component is separated from the next by a space

Translation:

d diagonal up line

iv.s vertical line down (iv) combined with a spin (s)

c ‘Half Cuban’ – half of a vertical figure 8

o normal loopThere are obviously many more of these terse one- or two-letter commands in the vocabulary. A sequence can be defined directly in the input window of the editor using these commands, and it will draw the appropriate figures and generate the Aresti catalogue numbers described above. (Alternatively, the table of Aresti figures is available in one pane of the editor, and clicking a figure in the table will insert that figure into the sequence.) In the OpenAero editor viscosity is very low, because the single line of terse commands makes it very easy to insert or delete symbols, and indeed this well-designed editor has special features to ease the process.

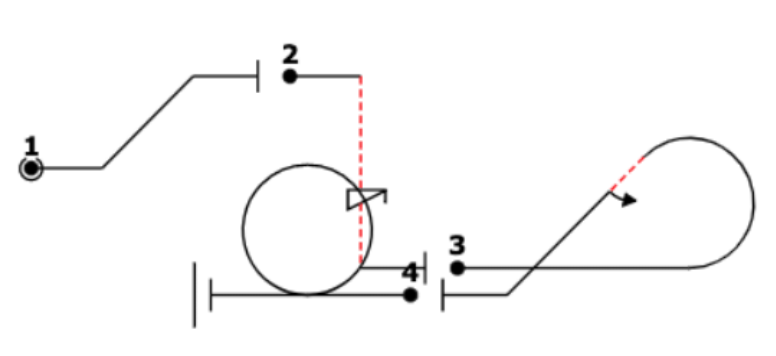

The OpenAero editor automatically generates a sequence diagram, but the chances are that the layout will need tweaking to improve the layout (Figure 5.). Additional spacing, line lengthening, and resizing is accomplished by directives that control the drawing, such as dots, commas, tildes, and percentages.

The well-laid out diagram of Figure 1. is created by the notational sequence of Figure 6., a shortened version of a sequence in the inbuilt library (2023, NZAC,Primary Known).

5% d ~~iv.s.'++~ -1% .....''c....,2....+~` 6% ~~~~~o~~~~~OpenAero notation for sequence of Figure 1. including drawing directives; compare with Figure 4.

At this point in notational development, we have reached Stage 4:

The stresses of using a rigid notation cause ‘decoupling’, in which a complementary notation is introduced as a sketching tool, before transcribing the sketch into the target notation.

If the notation is computer-based, a patchwork of improved helper tools appears, which reduce local viscosity; ....

Part 5If the notation is computer-based, a patchwork of improved helper tools appears, which reduce local viscosity; ....Indeed, we have started on Stage 5, in which “New notations are devised at a higher level of idealisation or abstraction”. Where the Aresti notation deals solely in basic elements of lines, curves, spins, and rolls, the OpenAero notation includes assemblages of those elements: ‘goldfish’, ‘shark tooth’, ‘humpty bump’,‘sausage’, and so on. Thus g, a ‘goldfish’, replaces the Aresti form7.3.2.1 9.1.2.2.At the same time, new possibilities become apparent: parentheses have been introduced to denote rolls during the execution of a figure, such as 2n(24)1 or 1dhd(2)(1)1 or dhd(2)(). Even without knowing what those expressions mean, it is clear that this notation works on a considerably higher level of abstraction than the original Aresti; furthermore, it is abstraction-tolerant– users can join figures into a subsequence, which can then be inserted as a whole into the sequence being created, or even into another subsequence. The abstraction manager shows each subsequence in a panel, and they can easily be opened and edited, thereby providing a simple reservoir, as we call it, to store fragments of sequences until their time is ripe.

What can we say of this new notation? Obviously it is very succinct (not verbose). Although we have no data we would expect it to be less error-prone than the Aresti codes. The closeness of mapping is rather better, with g for ‘goldfish’ or o for loop. Secondary notation is still entirely absent. In the context of real use, none of these issues may be problematic.

One last point. As we said earlier, the Aresti notation is history-sensitive:sometimes a code that is syntactically well-formed is semantically unacceptable, because the aircraft is in the wrong state (eg inverted when it needs to be upright), and we pointed out that checking for problems like that would be tedious and error-prone. The OpenAero editor addresses that issue by inserting an ‘auto-roll’ where needed, to put the aircraft in the correct attitude, meanwhile notifying that it has done so. Although, once again, we have no data, that seems a very good solution.